I saw Citizen Kane for the first time this week. Yesterday, to be precise. Not to review a thousand-year-old relic, but it’s very easy to understand why it is often said to be the greatest film ever made.

But I don’t want to focus on the sheer brilliance of the story or the success of it, today.

I want to focus a bit more on how it got made, and the interesting elements of how those things could be directly responsible for its success.

First, the best film ever made was made nearly a century ago

Talking to my sister about the film, I told her that making a movie like that would have been a dream—in many ways, it was my dream, that is until yesterday, to tell the most honest moving picture story possible about the human condition. Now I have to find another dream, because somebody else already did it 83 years ago, and almost 60 years before I was born.

I also found it interesting that Orson Welles was just 25 years old when he directed it.

On one hand, it is astounding that he had so much material to discern wisely at that age (although Citizen Kane was loosely based on some real-life businessmen and media moguls living in his time. Welles also co-wrote the screenplay with Herman J. Mankiewicz).

On the other hand, his resounding success at such a young age also made me think about something else—something Welles himself speaks about concerning that time.

Not knowing it was meant to be impossible helped him achieve it.

Welles thinks his inexperience—it was his first ever feature film—helped him by letting his imagination run free, as he didn’t have the expertise to know that what he was attempting was supposed to be impossible, or groundbreaking.

Speaking on where he found the confidence to direct Citizen Kane, he said:

“Ignorance … sheer ignorance. There is no confidence to equal it. It's only when you know something about a profession that you are timid or careful.”

Welles’ cinematographer while he was shooting the film also helped his confidence.

A seasoned veteran who was considered one of the greatest cameramen of his time, Gregg Toland told Welles that there was nothing about camera work that any intelligent person couldn’t learn in half a day.

“The great mystery that requires twenty years (to learn) doesn’t exist—in any field”, Welles went on to say in an interview talking about Toland’s influence on his confidence.

You can watch the video where he talks more about that here:

Meanwhile, something else I found remarkable about the story around this famous story is one we don’t hear too often.

The ‘greatest film ever made’ flopped

Alright, not flopped.

But although it was a critical success, Citizen Kane failed to recoup its costs at the box office. Now, of course, it was a fairly expensive project to make (an initial $500,000 budget, which rose to almost $840,000— about $17.6m in today’s money). But then again, money was not even remotely the goal of the project. RKO Pictures had cash to throw around at the time and were looking to add some brilliant, independent, “artistically prestigious films” to their roster.

The film was a sleeper hit too.

In fact, it didn’t make back its budget during its theatrical run. It left theatres quickly and even though it was groundbreaking, it performed underwhelmingly in terms of attracting audiences. It wasn’t until foreign critics rediscovered the film that it was then re-released in theatres.

I was just thinking about how big an effect reviews and critical opinions of a piece of work have on the perception of the work itself. If it is not seen favourably, it won’t last long in the public consciousness, meaning fewer people get to discover it for themselves, and its definitive reputation becomes the opinions of its loudest viewers.

Also, to hell with money, right?!

But yeah, Welles was given a great budget to work with and was given a pass when he exceeded, because he was trying to use the latest and greatest photographing techniques and was suffering from acute perfectionism.

Which brings us to our last point:

No film in 2024 should be worse than Citizen Kane

The story was made on equipment, that despite its technical advances for its time, so often struggled with light—underexposure, limited aperture, and other photographing elements that would be considered primitive to battle with for many videographers working in 2024.

The quality, though timeless, was expectedly characteristic of a film that was made mid-World War II. Grainy, monochrome, with fine details sometimes outrightly illegible.

And yet, the story was so colourful.

It remains so nearly a century later.

And it just makes me wonder. If it was all about technology, no film should be worse than Citizen Kane.

No film from the 60s, or the 70s, let alone the 2000s and 2010s, should be harder to watch.

But we know that to not be the case.

This is a testament, once again, that no matter how much technology changes our medium of expression, the intangible quality of writing, narrating, storytelling, trumps all.

Nine other things worth sharing

Sometime last year, when AI was seemingly going to take over our lives, I thought about how that revolution could affect my workflow, suite of apps and so on. One of the things I was mulling at the time was the possibility of Apple integrating AI features into one of my favourite productivity apps, Notes. I use Notes for everything, including everything. So I decided to work on a UI for what it would look like if Apple introduced Generative AI, spellcheck and other features to their prized application. You can see the designs, and read the process on my medium blog.

Read this analysis from Data Dive by Dataphyte that shared some information about single motherhood, singlehood and more in context to women. Two key things from the report stood out:

First, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest % of single mothers worldwide (32%).The other insight was the last sentence of the article, which goes:

On average, women are fertile for 72 days a year, but men are fertile 365 days a year. A man can impregnate at least 365 different women in a year if he has sex every day, but a woman can only get pregnant once a year. Who should be taking contraceptives?

Meta had a 25% YoY revenue increase, a 200+% net income increase (also year on year), and added $200bn to its market cap in ONE day.

It has never happened before in history. Scott Galloway’s METAstasis article talks about how, although Meta is posting generational earnings, it shouldn’t absolve them of their responsibility to the public, especially concerning teenage health and use. One excerpt of the article:Money is a mechanism for the transfer of time, work, and services. It’s a wonderful thing. You can pay your kids with housing and food so they are freed up to go to school and play. You can pay for your husband’s living expenses so he has the time to take care of the kids. And you can pay someone to do things that would take you more time to do yourself. Meta and the rest of the Big Tech companies create extraordinary economic value. This is important and can justify some externalities. Some. In America, however, we have chosen prosperity over progress.

Check out this Rowan Cheung X thread of the 7 most important developments in Generative AI recently.

Spotify CEO explains why artists get terrible payouts and why, despite the fact that the company is paying out its best historically, some artists still won’t earn more because of the simple fact that music, just like nearly everything else in the creative industry, is hard to do profitably if you’re not doing it at the highest level.

I read Changing Your Mind by Deb Liu

An excerpt from it:For all our talk of humility, as humans, we have a hard time admitting when we’re wrong. We seek in our leaders and politicians a type of consistency that we ourselves cannot achieve.

And it made me think more about everything else about how we act. Sometimes, we find it hard to even admit when we KNOW we are wrong, just because we don’t like the tone of the person we should be apologising to (your boss, spouse, child, or colleague). And yet, we expect utmost humility from public officials and other people with a responsibility to take our matters seriously in a varied capacity.

I also read How I Am Building My Own One-man Media Company by Alex Mathers

Just a thought to share:

Do you know that sometimes, you train yourself so much in learning to absorb and learn from failure, that you unknowingly begin to only imagine yourself in scenarios where you fail?

And so, somehow, you stop fearing failure and actually begin to fear success.

Because you know what to do when you fail. But you don’t know what to do when you succeed, and that lack of preparation makes you feel the need to gravitate towards what you know best. A home run scares you more than a Hail Mary. If you didn’t feel prepared enough, at least you knew there was a possibility to fail. But when you see a chance you can simply score, you think it to be some kind of trap and the simplicity of it all overwhelms you.

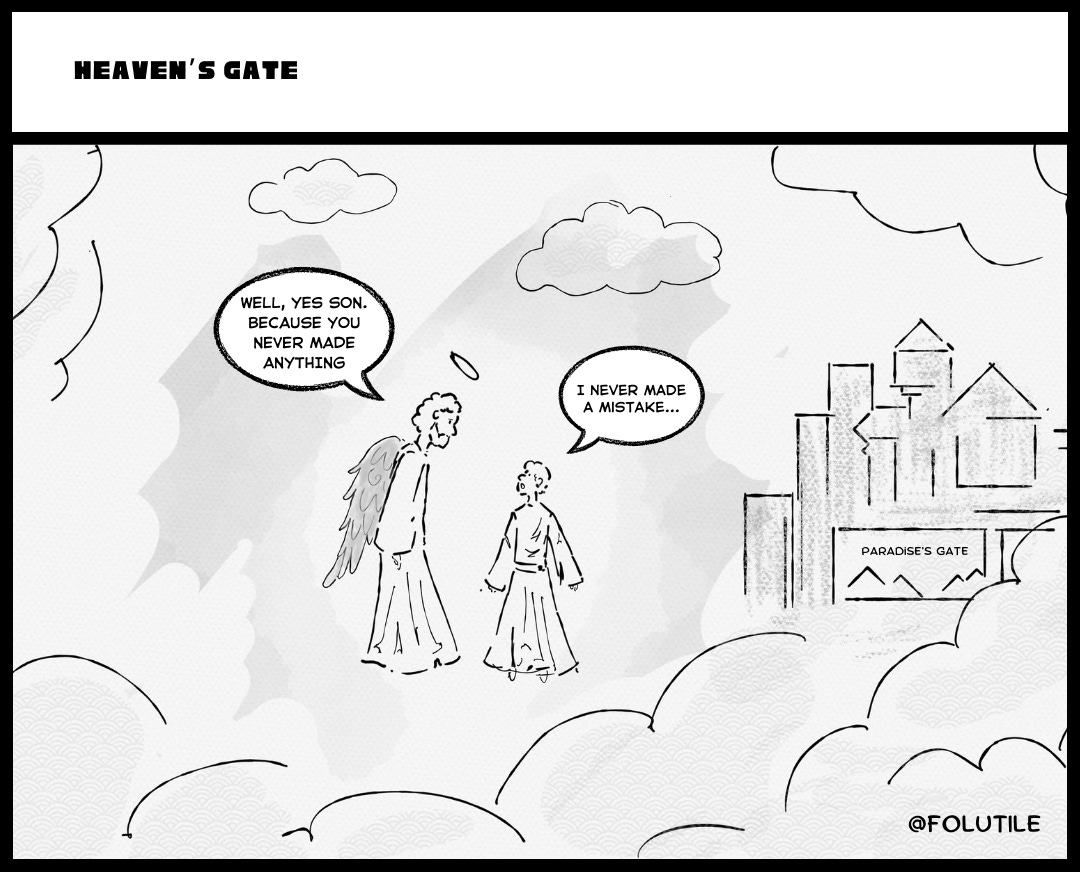

I made this earlier yesterday/today:

Citizen Kane was such a difficult movie to make that there are movies about it. Even getting the writer to put down the script was difficult, plus the alleged subject of the movie didn't want it to get made and a host of other issues. It definitely required someone with the unwavering belief that making the movie was possible to get it done.